by Meg-alodon

My mom’s death was preventable.

My mom died of a treatable disease.

My mom struggled with her illness for years but never found a treatment that worked for her.

My mom was ashamed of her illness.

My mom suffered from clinical depression.

My mom died by suicide.

My mom lost her battle with depression exactly three years ago. She had fought with her depression for at least ten years. As the years passed, I watched her slowly fade away, eroded by her depression. Her energy waned. Her spirit deflated. She acted without thinking and was, at times, self-destructive. My mom lived in a state of chronic pain – not physical pain, but emotional pain. She tried various medications, attended therapy, self-medicated with alcohol, but despite her efforts, she never found the right combination of medications and treatments that worked for her. Convinced that there was no other way to end her pain, my mom killed herself.

My mom tried to tell me that mental illness is similar to cancer, diabetes, or any other chronic disease. You can fight it, but nevertheless, you may still succumb to it. I didn’t understand. I thought that if my mom really wanted to, that if she worked hard enough that she could get better. No one told me otherwise. And why would they? No one talks about mental illness; no one talks about suicide. (Even at my mom’s funeral, no one mentioned suicide; we just skirted around that issue).

Both mental illness and suicide are severely stigmatized in our culture. Health insurance plans offer meager mental health benefits at best. Life insurance policies don’t pay out in the case of suicide. Suicide itself used to be a crime – individuals would be arrested for attempting suicide. Religious officials (particularly of the Christian faith) have only recently stopped preaching that suicide is a one-way, non-stop flight to Hell.

But today, let’s talk about suicide. Not only because my mom died by suicide, but because:

- Suicide is the tenth most common cause of death in the U.S. and the second most common cause of death in 15-29 year olds [1].

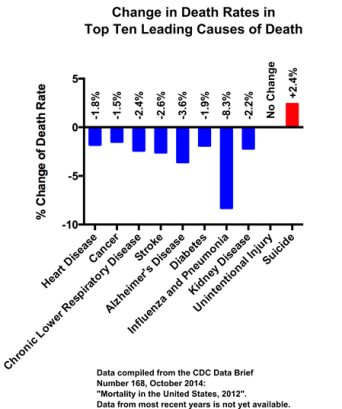

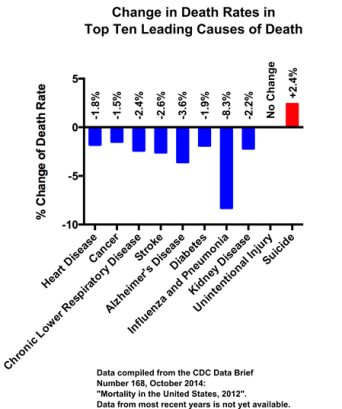

- Out of the ten leading causes of death in the U.S., suicide is the only one that has increased in the past five years (see graph below) [1].

- Each year in the U.S., about 650,000 people attempt suicide and 41,000 people complete suicide. (That’s more than four times the number of deaths due to Ebola last year!! [3]).

- One suicide happens every 12.8 minutes [2].

- Suicide costs the U.S. about $50 billion each year in health care costs and lost earnings [2].

What is the highest risk factor for suicide? Having a mental illness. In fact, over 90% of people who die by suicide suffer from a mental illness at the time of their death. Depression and bipolar disorder are the most common mental illnesses associated with suicide, but drug abuse, schizophrenia, and personality disorders also contribute to suicide risk [4]. Family history of suicide also increases an individual’s likelihood to die by suicide. Furthermore, 10% of suicides are copycat suicides (also termed contagion suicides) [4].

Contrary to common stigmas, mental illness is not a sign of weakness. It is not an indicator that an individual is unable to cope with the stressors of everyday life. Mental illness is not the fault of the person suffering from the disease. (It is unfair and illogical to blame someone suffering from cancer, for example, for the onset and continued progression of their illness, so why attribute mental illness to some flaw of the ill individual?)

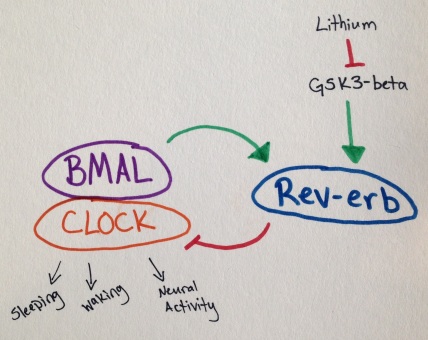

Mental illness is real and is based in physiological brain alterations. In depression, the most common brain alteration is an imbalance of the chemicals that help control mood, energy, and pleasure (these chemicals are named serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine)[6-9]. This chemical alteration has been observed during autopsies of the brains of suicide victims and can sometimes be observed via live brain scans and blood tests of severely depressed and suicidal individuals [5,6,9].

What causes decreased levels of the above chemicals? Scientists and doctors aren’t sure, but there are a number of plausible, medical explanations including genetics, brain injury, and many more. Even though we don’t know exactly what causes depression, we do know that depression is a biological illness [5].

Unfortunately, scientific research of mental illnesses is progressing slowly and is underfunded. Why? Because people don’t talk about mental illness. Because mental illness is not viewed as a crucial research topic despite the increase of suicides in recent years.

People who suffer from depression or any other mental illness deserve answers and better treatments, but most of all, they deserve compassion and understanding. My biggest regret thus far was failing to understand my mom’s illness while she was alive and not giving her the compassion that she deserved and so desperately needed. Now, I have compassion. Now, I am understanding. Now, I am not afraid to talk about suicide. Let’s start a conversation. Who’s with me?

For more information, please visit The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention at www.afsp.org.

This piece is dedicated to my mom. Miss you lots and love you always.

References:

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Mortality in the United States, 2012”. NCHS Data Brief Number 168, October 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db168.htm#lcod.

[2] American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “Facts and Figures”. Understanding Suicide. http://www.afsp.org/understanding-suicide/facts-and-figures.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa”. Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease). http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/index.html.

[4] American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “Key Research Findings”. Understanding Suicide. http://www.afsp.org/understanding-suicide/key-research-findings.

[5] Dwivedi, Y., Editor. The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2012.

[6] Bach, H., & Arango, V. “Neuroanatomy of Serotonergic Abnormalities in Suicide”. Dwivedi, Y., Editor. The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2012.

[7] Chandley, M.J., & Ordway, G.A. “Noradrenergic Dysfunction in Depression and Suicide”. Dwivedi, Y., Editor. The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2012.

[8] Meyer, J.H. “Neuroimaging High Risk States for Suicide”. Dwivedi, Y., Editor. The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2012.

[9] Pandey, G.N., & Dwivedi, Y. “Peripheral Biomarkers for Suicide”. Dwivedi, Y., Editor. The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2012.